Three Musketeers (1916)

The Three Musketeers

Rating: ***

Origin: USA, 1916

Director: Charles Swickard

Source: Alpha Home Entertainment DVD

This very early version of Alexandre Dumas’s greatest swashbuckler is enjoyable and, at only 50 minutes long, very fast-paced, though it only adapts the first half of the novel, the affair of the queen’s diamond studs. D’Artagnan is active, Richelieu is imposing, and Queen Anne is majestically pouty. As will be typical of American film versions to follow, it makes d’Artagnan’s love interest Constance into something other than Bonacieux’s wife—in this case, his daughter—and had Rochefort play both his role and that of the Comte de Wardes, which occurs in almost every film version. A good early effort.

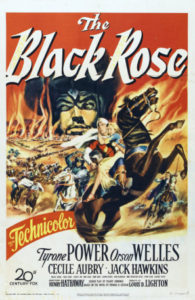

This movie works well as a spectacle depicting 13th-century England and parts of Mongolia and China. As an adventure or character-driven story, however, it’s not so good. This is one of those films in which the angry and stubborn protagonist is told at the beginning what he needs to do to find peace and purpose, spends the next two hours determinedly rejecting that advice, before finally embracing it in the last ten minutes of the picture. Lame! In this case, Walter of Gurnie (Tyrone Power), an illegitimate son of a Saxon lord, is the angry protagonist who’s suffered injustice at the hands of his Norman relatives. Edward II (Michael Rennie)—the King of England, no less—tells Walter he needs to put aside his hatred of the Normans for his own good and that of the realm and its people, but Walter angrily insists on leaving England to seek his fortune in distant lands—in far Cathay, if necessary, which he heard about from his Oxford mentor, Roger Bacon.

This movie works well as a spectacle depicting 13th-century England and parts of Mongolia and China. As an adventure or character-driven story, however, it’s not so good. This is one of those films in which the angry and stubborn protagonist is told at the beginning what he needs to do to find peace and purpose, spends the next two hours determinedly rejecting that advice, before finally embracing it in the last ten minutes of the picture. Lame! In this case, Walter of Gurnie (Tyrone Power), an illegitimate son of a Saxon lord, is the angry protagonist who’s suffered injustice at the hands of his Norman relatives. Edward II (Michael Rennie)—the King of England, no less—tells Walter he needs to put aside his hatred of the Normans for his own good and that of the realm and its people, but Walter angrily insists on leaving England to seek his fortune in distant lands—in far Cathay, if necessary, which he heard about from his Oxford mentor, Roger Bacon.