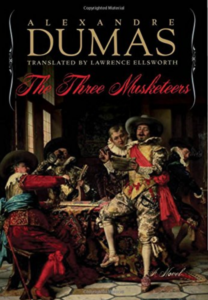

Book One of the Musketeers Cycle

By Alexandre Dumas, Edited and Translated by Lawrence Ellsworth

The Three Musketeers: Lawrence Ellsworth’s vibrant new translation of Alexandre Dumas’s most famous work, following the adventures of the valiant d’Artagnan and his three loyal comrades Athos, Porthos, and Aramis, as they pit themselves against the wily Cardinal Richelieu and the devious Milady de Winter.

Available Now in hardcover, trade paperback, and ebook formats.

In March of 1844, the Parisian paper The Century began publishing installments of a new tale by France’s favorite author, Alexandre Dumas. Week after week readers thrilled to the adventures of the brave and clever d’Artagnan and his loyal comrades. Collected for book publication at the end of that year, and quickly translated into a dozen languages, The Three Musketeers was a worldwide sensation—nowhere more so than in the United States. Citizens of the brash new republic recognized kindred spirits in the bold musketeers, and the book and its sequels found an eager American readership.

The novel’s fast-moving story is set in the royal court of Louis XIII, where the swaggering King’s Musketeers square off against their rivals: the crimson-clad Guards of the dreaded Cardinal Richelieu. The Red Duke rules France with an iron hand in the name of King Louis—and of Queen Anne, who dares a secret love affair with France’s enemy, England’s Duke of Buckingham. Into this royal intrigue leaps the brash d’Artagnan, a young swordsman from the provinces determined to find fame and fortune in Paris. Bold and clever, in no time the youth finds himself up to his Gascon neck in adventure, while earning the enduring friendship of the greatest comrades in literature, the Three Musketeers: noble Athos, sly Aramis, and the giant, good-hearted Porthos.

Now from Lawrence Ellsworth, acclaimed translator of The Red Sphinx, comes a new rendition of The Three Musketeers for a new century, one that captures anew the excitement, humor, and spirit of Alexandre Dumas’s greatest novel of historical adventure. Whether you’re meeting the musketeers for the first time or discovering them all over again, it’s all for one, one for all, in this timeless tale of honor and glory, the flash of dark eyes, and the clash of bright steel.

Introduction to The Three Musketeers by Lawrence Ellsworth (abridged):

The Three Musketeers is one of the best-loved novels of the 19th century, still read and admired over a century and a half since its first publication. It’s been a pleasure and a privilege to prepare a new, contemporary English translation of this novel, not least because it’s a work that has always meant a lot to me personally. Writing an Introduction to Dumas’s great classic is more than a little intimidating for this editor, but it’s worthwhile to consider where this book comes from, and why it’s still relevant and still resonates with readers in the 21st century.

The author, Alexandre Dumas, was a man who embodied contradictions: his immediate ancestors included both black Haitian slaves and white French aristocrats, he was a republican man of the people who wrote tales of kings, queens, and knights, and a devout admirer of literary lights like Shakespeare and Molière who innovated a collaborative, almost assembly-line method of writing that churned out industrial quantities of prose. Nearly everyone who met him remarked on his larger-than-life personality and unquenchable joie de vivre, his endless appetite for good food and wine, political debate, dramatic stories, and romantic women. Dumas contained multitudes, and in a way each of his four famous musketeers represented a part of himself—and one other.

After several histories and moderately-successful novels, by 1844 Dumas was ready to start work on two novels that embodied themes close to his heart, ideas he was passionate about because they represented, each in its own way, aspects of his beloved father’s life. The first of these two novels was The Three Musketeers, and the second was The Count of Monte Cristo.

To consider the second one first, The Count of Monte Cristo is the story of a good man unjustly imprisoned by a Napoleonic-era conspiracy, a man who escapes his fate and exceeds the limitations of his birth and incarceration to become an accomplished financier, a superb swordsman, a talented impresario, and a suave and celebrated member of high society—and who then employs these accomplishments as weapons to wreak vengeance on those who betrayed him. It’s Dumas’s homage to the successes of his by-his-bootstraps father, and payback for his downfall, an extended revenge fantasy that condemns the casual corruption of the European establishment while simultaneously craving its approval. It’s a powerful novel, still popular today, and with good reason—but once its story is told Monte Cristo’s tale is over, and Dumas never wrote a sequel to it.

But if The Count of Monte Cristo is Dumas’s dark revenge for France’s mistreatment of his father, The Three Musketeers is his tribute to the light of General Dumas’s heroism and courage, as incarnated in the persons of its protagonists, d’Artagnan, Athos, Porthos, and Aramis. The question of how men of courage could live their lives guided by personal codes of honor despite the conflicting dictates of society was a theme that had been percolating in Dumas’s work for some time. To really explore it, he just needed to find a framework grand enough to support full expression of the idea, a broad tapestry with scope enough for nuance and variety. The first few chapters of The Three Musketeers began appearing in the Parisian paper Le Siècle in March of 1844, and it was an immediate sensation.

The century from 1830 to 1930 was the golden age of historical adventure fiction, when mass publication in inexpensive books and periodicals brought such stories to millions of readers, and in Europe and America historical tales were arguably the leading form of entertainment. Novels with heroes toting swords, bows, and muskets appeared by the thousand, most to be read once, quickly, and then tossed aside. Out of all these many, many tales, why has The Three Musketeers endured? Certainly its incidents are exciting and well-told, but the plot connecting them rambles at times, especially in the middle chapters, betraying the tale’s origins as a weekly serial. In the end, what sticks with us are the characters of the four musketeers (d’Artagnan included in that number from chapter forty-eight on), their distinct personalities, and the amusing and endearing ways they react to the dilemmas posed by their adventurous lives. Best of all is how they use their varying strengths and skills to support each other through every trouble and trial.

At every challenge, one of the musketeers steps forward to lead the response, and the others line up behind him to face it as a unit. “All for one, and one for all”—the famous motto appears only once in the novel, but it’s put into practice again and again. Each of the musketeers is an archetype, embodying a set of virtues useful to the team as a whole. This has fictional precedent in the Knights of the Round Table and, particularly, Robin Hood and his Merrie Men, but never before had these knightly virtues been crystallized and encapsulated so winningly as in the four musketeers. These four remarkable personalities weren’t the invention of Courtilz de Sandras, whose characters are little more than names, they were born from the inspired genius of Alexandre Dumas. And the source of his inspiration was that each of the four embodies an aspect, at least as he saw it, of his father, General Thomas-Alexandre Dumas.

There is Athos, the exemplar of the virtues of the old nobility, who lives by the laws of chivalry of an earlier era, and though bound and blighted by the strictures of his medieval code of honor, is compelled by that code to an unfailing generosity that uplifts everyone it touches. Though entitled to answer to the ancient name of the Comte de La Fère, he feels forced by circumstances to hide it under the simple name of Athos—as General Thomas-Alexandre did when, estranged from the noble side of his family, he took his mother’s name of Dumas and set aside the name of Davy de La Pailletrie, to which he was entitled as his patrimony.

There is Porthos, who like the general is a giant in both size and strength, a man of boundless energy whose vanity is offset by his inexhaustible good humor. Porthos, younger son of the bankrupt petty gentry, who has no prospects and nothing but what his strength and ambition can win for him.

There is Aramis the sly and calculating, the least like General Dumas and thus the least likeable, though he shares the general’s appetite for romance and the company of women. Aramis is the most bloodthirsty of the four—when the musketeers get involved in a fight, it’s always his opponent who ends up dead—and of the four friends he’s also the aspiring writer, though that’s an aspect of the younger Dumas rather than the elder. Aramis is the most complex of the four, and therefore, by the tenets of the Romantic movement, the most compromised.

First and last, there is d’Artagnan. D’Artagnan the tactician, quick-witted and far-seeing, whose bold plans seize the initiative and win the day. D’Artagnan the sensitive, who sees past people’s surfaces and self-deceit to perceive the feelings and motivations beneath. D’Artagnan the natural leader, who despite his youth has an innate feel for command, and the confidence that others instinctively follow. Most of all, he is d’Artagnan the soldier, and his career will embody the triumphs and disappointments of a soldier’s life.

And careers they will have, all four of them—because in these four exemplars, these four facets of the gem of human character, Dumas created his ideal vehicles for addressing what he saw as the central challenge of a life worth living: how to find the courage to adhere to a personal code of honor in the face of pressure from society and oppressive authority. How, in short, to do right. It’s a problem it takes a lifetime to solve, which is why The Three Musketeers has a long series of sequels where The Count of Monte Cristo does not. History moves onward, the musketeers’ lives march on, and each of them wrestles with the challenge of honor in his own way, ultimately both succeeding and failing according to their natures. And herein lies Dumas’s true genius, for from beginning to end, each of these enduring characters is uniquely and loveably himself, imbued with Dumas’s deep love of life and humanity, and marching to the heartbeat of a father’s love for his children.

A Note on the Translation: Why do another English translation of The Three Musketeers, especially when there are fine recent renditions by Richard Pevear and Will Hobson? Because it deserves it, and because most published editions of the novel that you’ll find in bookstores and libraries still use translations that were prepared in the 1840s or 1850s, respectable but creaky adaptations endlessly recycled and reprinted, versions that simply don’t properly convey the energy and tone of Dumas’s original work. Though to be fair, those Victorian-era translators knew their business, and delivered exactly what their readers were looking for: historical dramas at the time were expected to be told in the stiff, elevated diction of writers like Sir Walter Scott and James Fenimore Cooper, and the translators saw it as their job to render Dumas’s unconventionally active prose into the more passive style then prevailing. But in doing so these early translations lost much of Dumas’s distinctive voice and tone, that warmth and vibrancy that leaps off the page in the original French. And that’s a real disservice to contemporary readers, denying them some of the key virtues of this really quite modern writer. In translating this, one of my favorite works of fiction, I felt my most important task was to identify Dumas’s genuine voice and bring it to current-day readers of English, so they can meet the man on his own terms and really appreciate what he has to offer.

The original novel exists in several variations; where there were inconsistencies, to resolve them I usually relied on the edition compiled by Charles Samaran for Éditions Garnier in 1956. Dumas wrote very quickly, and sometimes character and place names vary in the original from one chapter to the next, when the author didn’t accurately remember what he’d written earlier in the process. For consistency and clarity I’ve regularized these variants, usually selecting the spelling that’s best-known or which is historically correct for the period. By the standards of the mid-19th century the novel took a rather frank approach to sexuality; those scenes, which were mostly or wholly elided from the Victorian translations, have been restored in this version. Not least importantly, I’ve also kept in all the jokes. Dumas was a very funny man, and I have no patience with translators who note that a gag “is a Gallicism that cannot be properly rendered into English.” Weak! Dumas wasn’t above stooping to make a terrible French pun, in which case I considered it my solemn obligation to provide some matching wordplay in English. Because literary translation is a noble calling, and sometimes your sacred duty to the reader requires you to make a terrible, terrible pun.