The Court Jester

The Court Jester

Rating: ***** (Essential)

Origin: USA, 1956

Directors: Norman Panama and Melvin Frank

Source: Paramount DVD

There were swashbuckler parodies before this film, and others followed later, but The Court Jester is the one and only crown jewel, the chalice from the palace, the brew that is true.

The film was produced, written, and directed by the team of Melvin Frank and Norman Panama, Hollywood journeymen who’d first made their mark with Hope and Crosby comedies in the forties. By the mid-fifties they’d been working together for years, and knew exactly what they were doing. Star Danny Kaye had made an impression with 1947’s The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, but followed that with a series of mediocre comedies that he felt didn’t show off his real strengths. Panama and Frank agreed, and formed a production company with Kaye to create for him a vehicle worthy of his array of talents.

The big studios had been churning out loud and hokey knights-in-shining-armor movies since about 1950, most of them bloated groaners ripe for parody. Panama, Frank, and Kaye decided some medieval mockery was in order, especially of the many knight-in-training films, but then had the inspired idea of borrowing most of their tropes from an actual good movie, the beloved 1938 Adventures of Robin Hood with Errol Flynn. As icing on the cake they even hired Flynn’s antagonist, Basil Rathbone, to play their leading villain.

And then they wrote a script that is a work of goddamn genius, an action musical that never lets up except to pause for the next comic song, with stock characters all spouting perfect parodies of Hollywood medieval bombast, interspersed with tongue-twisting vaudeville fast-talk routines and punctuated by hilarious physical comedy, all driving an intricate plot that has seventeen moving parts that somehow all interweave and mesh perfectly.

And at the center of this controlled chaos, the focus and fulcrum of almost every scene, is Danny Kaye’s Giacomo the Jester, mugging, swaggering, cowering, singing, japing, pratfalling, and blustering in the performance of a lifetime, somehow simultaneously evoking Laurel and Hardy, Abbot and Costello, Charlie Chaplin, and Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. (Whew!)

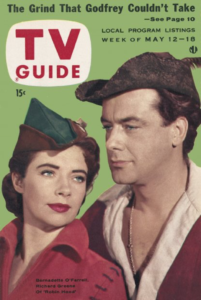

Moreover, as if Kaye and Rathbone aren’t enough, we also get the spirited and gorgeous (and slyly funny) Glynis Johns as Kaye’s romantic and comedic foil, a glowing Angela Lansbury as a spoiled and self-centered princess, and the under-rated Mildred Natwick nailing the whammy as the princess’s sorcerous servant. Plus there’s a Robin Hood-style masked outlaw, a secret passage, a baby in a basket, a troupe of midget acrobats, and a vessel with a pestle. If you haven’t seen it, you must. Get it? (Got it!) Good.