Scaramouche (1952)

Scaramouche

Rating: ****

Origin: USA, 1952

Director: George Sidney

Source: Warner Bros. DVD

Born in Italy, the author Rafael Sabatini had lived in England since 1892—but when the First World War broke out, faced with Italian conscription, he finally naturalized, then served throughout the war as a translator for British Intelligence. Though he never said why, working for the spy service darkened Sabatini’s worldview, and when he returned to writing after the war, his first novel was the bitter and scathing Scaramouche (1921), a best-selling story of romance, revolution, and above all, revenge. This MGM adaptation leaves out most of the politics, but the romance and revenge are front and center.

“He was born with a gift of laughter, and a sense that the world was mad”: the famous first line of the novel, inscribed as well on Sabatini’s tomb, also starts the film—though it will be awhile before we see the protagonist to whom it applies. First we’re introduced to the Duc de Maynes (Mel Ferrer), a sneering aristo whose hobby is picking fights with other men and then slaying them “honorably” in sword duels. The duke is gently scolded for this lethal pursuit by the Queen of France, who thinks he needs to settle down, and selects one of her demoiselles, Aline (Janet Leigh, radiant), to be his future bride. Her Majesty also complains about the rude political pamphlets written by the revolutionary who uses the pseudonym Marcus Brutus, and the duke vows to discover and deal with him in his usual fashion.

Background established, we finally meet André Moreau (Stewart Granger), a scapegrace young wit, romancer, and philosopher of life, paying a midnight visit to a traveling Commedia dell’Arte troupe to make love to its leading lady, Lenore (Eleanor Parker). Moreau is also besties with Philippe de Vilmorin, who’s secretly that Marcus Brutus being pursued by the duke’s goons. Moreau promises to help him, but is unable to prevent de Maynes from maneuvering Philippe into a duel and killing him before his eyes. Moreau swears to avenge Philippe, but barely escapes himself, and is forced to hide in Lenore’s comedy troupe, adopting the impudent rôle (and impudent mask) of Scaramouche. The laughing scoundrel finds a purpose at last.

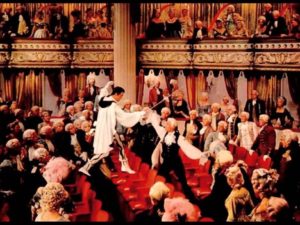

Though Granger, when he came to MGM, stipulated in his contract that he get the lead in Scaramouche, he’s not ideal for the rôle: his mockery is joyless, and he lacks the comic touch for his bits with the Commedia. In short, he’s not funny enough for Sabatini’s scornful clown. And the less said about his unconvincing love scenes with Leigh and Parker, the better. However, Granger brings two powerful assets to the part, a feel for grim vengeance, and the skilled swordplay that’s central to the movie’s final third. There are fine learning-to-fence montages as Moreau trains with two master swordsmen, scenes that reflect the serious training Granger himself undertook in preparation for the picture. He does his own stunts, and both Granger and Ferrer (a dancer, and it shows) do all their own fencing, most notably in the justly-famous seven-and-a-half-minute duel in a Paris theater that serves as the climax of the story. That duel alone is worth the price of admission, and is a thoroughly satisfying payoff to the ninety minutes of set-up that give it weight. Trust me, it’s probably the best scene with a hero wearing skin-tight striped leggings in all of cinema.