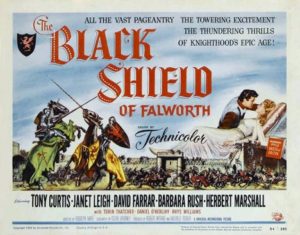

Black Shield of Falworth

Black Shield of Falworth

Rating: ***

Origin: USA, 1954

Director: Rudolph Maté

Source: Amazon streaming video

The Victorian children’s novel Men of Iron (1891) by the American author and artist Howard Pyle was influential in solidifying the tropes of the “knights in shining armor” medieval adventure tales popular right up through the 1950s. Pyle’s story was a simple morality play in which Myles, a young Englishman whose father was betrayed by an ambitious noble, trains as a squire and then as a knight, finally avenging his father’s betrayal. Pyle’s vivid depiction of would-be knights training with sword, shield, armor, and lance was recycled countless times in tales of medieval chivalry over the next three-quarters of a century. Men of Iron also established in popular fiction the conventions of trial by combat (“And may God defend the right”), the favorite climactic plot device of the lazy knight-pulp writer.

All of these tropes are on display in classic fashion in Falworth, Universal’s adaptation of Men of Iron. Concocted as a star vehicle for Tony Curtis, in his first big-budget epic, Pyle’s simple tale is simplified even further for the screen, while its romance aspect is fleshed out to provide additional screen time for the radiant Janet Leigh, Curtis’s wife, in the rôle of the female romantic lead, Lady Anne. Curtis’s nimble athleticism serves him well in the part of the hot-headed and energetic Myles, though when reading his lines his delivery is still sometimes embarrassingly amateurish. It doesn’t help that a lot of the dialogue is in the highfalutin elevated diction considered appropriate for tales of medieval chivalry ever since Sir Walter Scott (e.g., “Have you not had your fill of buffoonery?”), but thankfully it’s toned down considerably from the language in the novel.

The guy who gets the best lines is Torin Thatcher—you know him as the sorcerer in 7th Voyage of Sinbad—appearing here as Sir James, the surly one-eyed master-of-arms-cum-drill-sergeant who trains Myles in the knightly martial arts. His is easily the film’s most enjoyable performance, clichéd though it may be, and when he barks a threat to hurl Myles from the battlements if he gets into another brawl, you believe him.

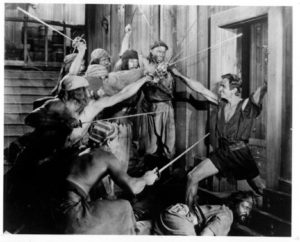

Falworth is Universal’s first Cinemascope extravaganza, and no expense was spared on the colorful costumes and expansive sets, with absurdly spacious castle interiors and grand courtyards where platoons of men-at-arms ply their medieval weaponry. The romance is familiar stuff, the villains’ plots are all too predictable, but the fight scenes are tight and well-choreographed, the whole thing is a pleasure to look at, and it doesn’t pretend to be anything but a simple tale of pluck and virtue triumphant over mean-spirited wickedness. (Oh, and by the way, persistent movie myth notwithstanding, Curtis never says,”Yonda stands the castle of my fadda”—for that, see “The Son of Ali Baba.”)