Silent Screen Swashbucklers, Part 1 of 2: Zorro Makes his Mark!

The Mark of Zorro (1920)

The swashbuckler tradition was born out of legends like those of the Knights of the Round Table and of Robin Hood, revived in the early 19th century by Romantic movement authors such as Sir Walter Scott. The genre really caught hold with the publication of Alexandre Dumas’ The Three Musketeers in 1844, and for the next century it was arguably the world’s leading form of adventure fiction, challenged only by the American Western.

The action and visual flair of the swashbucklers were perfect for the movie screen, and Hollywood brought them to life with brio and panache, starting most successfully with lavish productions of The Mark of Zorro (1920) and The Three Musketeers (1921), both starring Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. The 1920s through 1950s were the heyday of the Hollywood swashbuckler, but they continue to find favor with moviegoers right up to the present, notably in the recent Pirates of the Caribbean series. So it’s worth going back to see how those visual tropes around the hero-with-a-sword were first established during the silent film era, because much of what you see on the screen today had its roots almost a hundred years ago with those early cinematic pioneers.

I had a good time surveying these early swashbucklers, and I hope you’ll enjoy this overview. With luck, it’ll even inspire you to dip into this rich source of adventure film tradition yourself.

1913

The Count of Monte Cristo

Rating: **

Origin: USA

Director: Golden/Porter

Source: Grapevine Video DVD

Alexandre Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo is a long and complicated novel, one of our greatest revenge fantasies, and even if you were adapting it from a truncated theatrical play version (as this was), trying to tell its story in just over an hour necessitates stripping it down to its barest skeleton. James O’Neill, who plays Edmond Dantes/Monte Cristo, had been famous for his stage production of the novel, and this is what he brought to the screen. The story moves right along (it has to), they moved a lot of the scenes to appropriate external locations, and it ends with some brief but satisfying swordplay. Still, as Monte Cristoadaptations go, this one’s pretty perfunctory.

1916

The Three Musketeers

Rating: ***

Origin: USA

Director: Charles Swickard

Source: Alpha Home Entertainment DVD

This very early version of Alexandre Dumas’s greatest swashbuckler is enjoyable and, at only 50 minutes long, very fast-paced, though it only adapts the first half of the novel, the affair of the queen’s diamond studs. D’Artagnan is active, Richelieu is imposing, and Queen Anne is majestically pouty. As will be typical of American film versions to follow, it makes d’Artagnan’s love interest Constance into something other than Bonacieux’s wife — in this case, his daughter — and had Rochefort play both his role and that of the Comte de Wardes, which occurs in almost every film version. A good early effort.

1920

The Mark of Zorro

Rating: ***** (Essential)

Origin: USA

Director: Fred Niblo

Source: Kino Video DVD

Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., on his way to Europe on his honeymoon after marrying screen darling Mary Pickford, had brought a stack of All-Story Weekly pulp fiction magazines with him to read during the crossing on the steamer Lapland. He was struck by the hero of Johnston McCulley’s The Curse of Capistrano — Zorro, of course — and decided that he’d found the subject of his next movie. The next year Fairbanks played the starring role in the story he’d re-titled The Mark of Zorro; it was a gigantic hit, and Fairbanks was to spend the next ten years as a movie swashbuckler, appearing in lavish productions as Zorro, d’Artagnan, and Robin Hood.

The Mark of Zorro is a genuinely great film, the movie that elevated Douglas Fairbanks from star to superstar. His athleticism and charisma are legendary, of course, but damn it, the man could act: his foppish Don Diego is as hilarious and nuanced as his heroic Zorro is rousing and romantic. The villains are also uniformly excellent: Robert McKim’s Captain Ramon is every bit as mocking and arrogant as Basil Rathbone would be later, and Noah Beery’s swaggering rodomontades as Sergeant Gonzales even steal the scenes he shares with Fairbanks.

All the elements of the Zorro legend are here, fully formed: the black mask and cape; the hidden cave under the hacienda; the mute servant, Bernardo; even the black stallion, trained to follow its master’s orders. Plus the action scenes are great — Fairbanks famously did all his own stunts — the cinematography and direction are sharp and free from the theatrical staginess that plagued a lot of the silents, and the period details are spot-on.

Not to mention that this film is indisputably the direct inspiration for the Batman. If you’re a Batman fan but haven’t seen The Mark of Zorro, you’re just not fully aware of that character’s origin.

1921

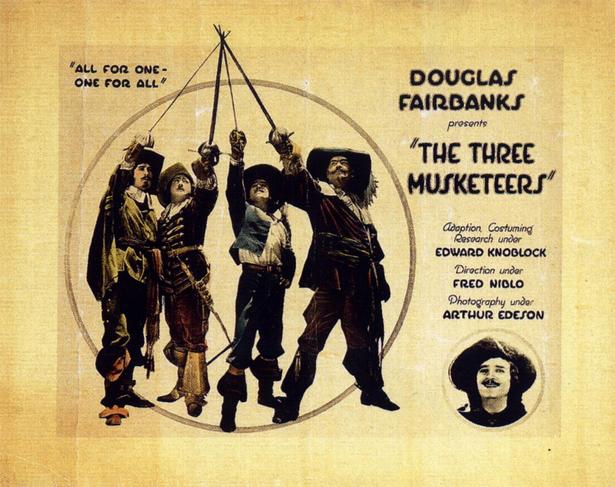

The Three Musketeers

Rating: ****

Origin: USA

Director: Fred Niblo

Source: Kino Video DVD

Douglas Fairbanks, Sr.’s Three Musketeers is far and away the best of the seven versions filmed in the silent era — but more about that in a moment. First I want to gush about this production’s costumes, which are fabulous, both historically accurate and theatrically gorgeous. This film was another Fairbanks production, and after the worldwide success of The Mark of Zorro, no expense was spared in an attempt to duplicate that triumph. And boy, did they succeed. The costumes and sets show that serious attention was paid to getting the details right, and I noticed settings and tableaux inspired by 19th-century paintings of the period, as well as the engravings of Maurice Leloir, Dumas’s most celebrated illustrator.

Fairbanks was nearly forty in 1921, far too old for the part of the youth d’Artagnan, but instead of trying to look young he plays young, in his expressions and body language, and does so brilliantly. Fairbanks made his Zorro an acrobat, and he does the same for d’Artagnan, leaping and fencing with a buoyant athleticism that has been attached to the rôle of the young musketeer ever since. But beyond that, Fairbanks’s d’Artagnan exhibits the sharp wits and quick thinking on display in Dumas’s novel, crucial aspects of the character that are often overlooked in lesser adaptations.

Once again, the film covers only the first half of the novel, the affair of the diamond studs, but with 121 minutes to do it, this version has much more room for character interplay, romance, and joyous musketeer shenanigans. There is roistering, roguery, and outright piracy on the English Channel. This time around Constance is Bonacieux’s niece rather than wife, and she gets a generous amount of screen time in a movie that’s otherwise a boys’ club. But the real supporting-actor prize goes to Nigel Brulier as Cardinal Richelieu, whom he plays as a cold and calculating automaton with a genuinely ominous screen presence. In the end Richelieu reacts to his defeat with dignity and even generosity, but is rebuffed by d’Artagnan and the musketeers, who prefer their camaraderie and half-drunken revelry to the sober demands of the state. You go, frat boys!

1922

Monte Cristo

Rating: **

Origin: USA

Director: Emmett J. Flynn

Source: Flicker Alley DVD

Another adaptation of Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo, a remake of the 1913 version, shot from the same basic script (to which Fox bought the rights), but greatly expanded for a film a half hour longer than its predecessor. Lead John Gilbert was a rising star at this point, though he hadn’t yet gained the popularity he would with The Big Parade (1925) and Flesh and the Devil (1926). Once again, Edmond Dantes succumbs to a conspiracy of envy and is imprisoned in the horrific Château d’If, only to escape and achieve his revenge, out-conspiring the conspirators as the chameleonic Count of Monte Cristo. The villains, each a different flavor of sleazy, are thoroughly despicable, and the innocent Mercedes, Dantes’s lost love, is wide-eyed and appealing. Gilbert looks and moves well in the rôle of Monte Cristo, and inhabits the count’s various guises convincingly.

This version avoids the stage-play feel of its predecessor by employing frequent close-ups and switching camera distance and angle often. And it does a better job of explaining how Dantes comes by, not just his great wealth, but also the knowledge and culture that enable him to pass as the elegant and noble count. With its extra running time, there’s room to include more of the characters and twists of Dumas’s novel, adding robberies, lurid murders, duels, and impersonations. In fact, it’s somewhat over-ambitious, trying to jam in more of the novel than is comfortable in less than two hours. In the end it feels too contrived, and not even a final spate of swordplay and highway robbery can quite save it. It’s just too hokey.

Rupert von Hentzau (Ramon Novarro)

The Prisoner of Zenda

Rating: ***

Origin: USA

Director: Rex Ingram

Source: Warner Bros. DVD

This film, the second silent movie adaptation of Anthony Hope’s best-selling 1894 novel, features craggy-faced Lewis Stone in the dual parts of Rudolf Rassendyll and King Rudolf, and Ramon Novarro, in his breakout rôle, as the villain Rupert of Hentzau. Every version of Zenda is stolen by the engaging rogue Rupert, and this is no exception — and Novarro’s raffish charm in the part made him a star. The movie starts slow, and its talky set pieces betray the production’s origins as a stage play, but the emphasis on interiors and close-ups gives plenty of scope for mugging by an array of fine silent-screen character actors. A great deal of effort was put into Ruritanian pomp and display that hasn’t aged well, and the story doesn’t really pick up until over an hour into it—but once the action starts, there’s actually more swordplay than in the better-known 1937 and 1952 versions. The last forty minutes definitely redeem the previous seventy, and the fencing in the final scenes is better than anything we’ve seen previously in the silent era. Visual Bonus: monocles and jodhpurs!

Robin Hood

Rating: **

Origin: USA

Director: Allan Dwan

Source: Kino Video DVD

After Douglas Fairbanks’s worldwide success with The Mark of Zorro and The Three Musketeers, no expense was spared for his next swashbuckler, 1922’s Robin Hood. The film is a spectacular saga of medieval chivalry, a lavish production on an epic scale, but is all about lords, ladies, and kings, with strangely little Robin Hood in it. It’s a weird boys’-club of a movie that’s mostly about the manly bromance between Fairbanks’s Earl of Hungtingdon and King Richard the Lion-Hearted, played with wearying brio by beefy Wallace Beery. Huntingdon is the knightliest knight when it comes to trouncing the others at tournament, but he’s strangely leery of the ladies, and when Richard tells him to take his prize from Lady Marian, he says (I am not making this up), “Exempt me, Sire. I am afeared of women.” Spoiler: he gets over it, as least as regards Marian.

There follows about an hour of royal intrigue involving King Richard, evil Prince John, and Huntingdon, as the king leaves England to lead an army to the crusades. There’s a fair amount of regrettable nonsense about militant Christianity marching off “with high purpose” to wrest the Holy Land from the infidels. However, once Richard leaves Prince John to rule as regent until he returns, John immediately becomes an oppressive tyrant who turns England into Mordor. Peasants are robbed of all they possess, women are abused, and capering torturers burn and lacerate for John’s dour amusement.

The movie’s more than half over before Huntingdon returns to England to set things aright by donning Robin Hood’s cap and tights. As a knight Huntingdon was stolid and earnest, but as Robin he’s suddenly as merry and active as Zorro and d’Artagnan. Fairbanks leaping like an acrobat was a revelation in The Mark of Zorro, but in Sherwood Forest a hundred Merrie Men imitating him and bounding about like springs is ludicrous.

In fact, I find Robin Hood the least effective of all the Fairbanks swashbucklers because it’s so overblown in every way. All the sets are colossal, every tableau is teeming with extras, the language is highfalutin and purple, and everybody over-reacts to everything. Every actor overplays his role (except Sam De Grasse as Prince John, whose relative restraint actually makes him seem more sinister). Except for Little John — played by the talentless Alan Hale, who will assume the role twice more over the next thirty years — the familiar Merrie Men barely make an appearance, and none of the famous tales are even referenced, so it barely resonates as a Robin Hood movie. And gah, the hairstyles are terrible.

The film was a big hit in its day, but I just I don’t find that it holds up particularly well 95 years later. I can’t recommend it.

1923

Scaramouche

Rating: ****

Origin: USA

Director: Rex Ingram

Source: Warner Bros. DVD

You know a film adaptation is good when it makes you want to go back and re-read the book. Scaramouche is a real gem, and a close adaptation of Rafael Sabatini’s novel, which had been a recent (1921) best-seller. The production has the same director and cast as the previous year’s Prisoner of Zenda, but with a swap at the top, Ramon Novarro cast as the romantic lead, André-Louis Moreau, and Lewis Stone taking the part of the supporting villain, the Marquis d’Azyr. It was a good move, as the fiery young Novarro was perfect for the role of Moreau/Scaramouche — in fact, much better suited than the rather stolid Stewart Granger in the better-known 1952 version.

It’s France under Louis XVI, and we’re back in Mordor again, with the populace ground down by the oppressive nobility. Many of the bloated aristocrats are hilarious caricatures — the Minister of Justice could pass for Baron Harkonnen. The movie starts out a little slow, establishing its characters and Moreau’s reasons for revenge on the aristos, but really gets moving once he’s on the run and joins a troupe of traveling actors. As a stage performer, Novarro gets to unleash his undeniable charm, and once he dons the striped outfit of Scaramouche we’re off to the races. The film spends an hour covering the same ground as the ’52 version — the first, more personal half of the novel — and then goes beyond into the politics, glories, and horrors of the French Revolution, which are depicted convincingly.

The costumes and make-up are superb, and in a series of dueling scenes we see the first really good fencing of the silent era, swordplay both persuasive and exciting. And instead of the usual contrived happy ending, the film is true to its source and retains the rather dark finish of Sabatini’s novel. Aux armes, mes camarades! Visual bonus: snuff boxes and quizzing glasses!

1924

The Sea Hawk

Rating: ***

Origin: USA

Director: Frank Lloyd

Source: Warner Bros. DVD

Pirates at last! The Sea Hawk features Wallace Beery as a piratical rogue a full ten years before his star turn as Long John Silver in Treasure Island. Here he also plays a loveable villain named Captain Jasper, opposite star Milton Sills as Sir Oliver Tressilian, who I’m convinced was cast mainly for his burning gaze and the fearsome way he slowly clenches his fist when contemplating revenge on his betrayers.

The story is based on Rafael Sabatini’s 1915 novel, which had been revived in the wake of the worldwide success of his Scaramouche and Captain Blood. This film hews much more closely to the novel than the later version with Errol Flynn. It tells the story with an old-fashioned melodramatic staginess that was already going out of style, especially in the movie’s first act, an Elizabethan soap opera (with dueling) that sets up why Tressilian, one of the queen’s former “sea hawks,” gets himself shanghaied onto a pirate ship. That’s when the rapscallion Beery enters the picture, and the real fun begins.

Suddenly, sea battles! And not filmed with models or miniatures, either, they built real ships for this, a barque and two galleys, and the clashes between them are pretty spectacular. Betrayed in England, made a galley slave by Spain, Tressilian renounces Christianity and joins the pirates of Algiers to take his revenge on the world. He becomes a corsair captain, and in due time he captures the rogue Beery who originally captured him. The two join forces, and rascally antics ensue. Also alarums, excursions, abductions, impersonations, leering lechers, spying eunuchs, and vengeance-turned-to-ashes-in-one’s-very-mouth. That slow and stagy start? All is forgiven.

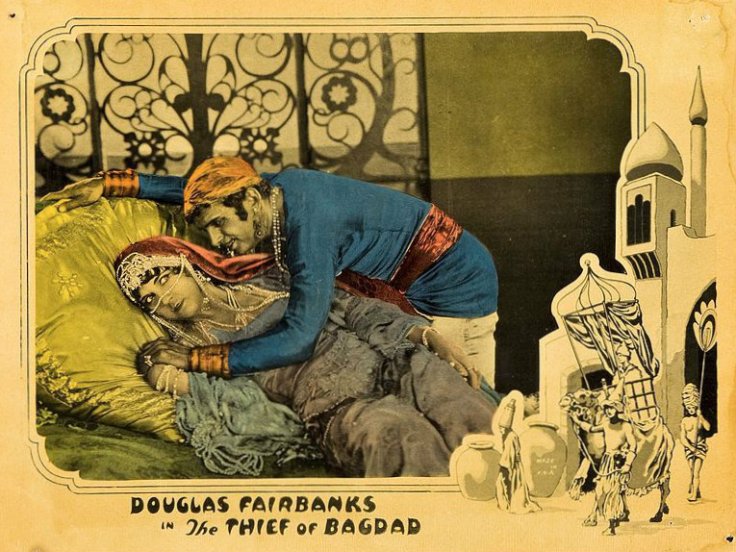

The Thief of Bagdad

Rating: ***** (Essential)

Origin: USA

Director: Raoul Walsh

Source: Cohen Film Collection DVD/Blu-Ray

Douglas Fairbanks gets his swashbuckling mojo back in this fabulous, dream-like fantasy that features the star at his most expressive and balletic, swaggering, leaping, and pantomiming through a fable from the Arabian Nights. The costumes are eye-popping and opulent, with towering hats — I mean, they look like actual towers — and curly-toed shoes to die for. The fanciful sets (by William Cameron Menzies) are fairy-tale tall and studded with grips so Fairbanks can clamber all over them. In its own way the film is as excessive as Robin Hood, but this time every excess is in service to the story, which moves quickly and stays focused, even with a running time of almost two and a half hours. A lot of the credit for this should probably go to the director, the great Raoul Walsh, in an early effort from a long career that would later include such classics as High Sierra and swashbucklers like Captain Horatio Hornblower.

Even after almost a century, the Thief’s visual gags in this film are outstanding, a combination of Fairbanks’s inspired gymnastics and some imaginative camera tricks. Fairbanks’s dancelike movements and broad gestures are compelling and eloquent, but he’s just as effective with his facial features in intimate close-ups. The star still had many fine films ahead of him — as we’ll see — but The Thief of Bagdad has to be regarded as his masterpiece.

The story, about wooing and winning a princess, is negligible, a flimsy pretext for infiltrations, escalades, abductions, and rescues involving such enchanted adjuncts as a fakir’s vertical trick rope, a flying carpet, and a wondrous winged horse. Also sleeping potions, mystic talismans, and a Valley of Fire. Plus secret panels, walking tree-men, giant bats, crystal balls, a cloak of invisibility, an underwater city of sirens, a spider the size of a grizzly bear, and the Old Man of the Midnight Sea. The film just keeps unrolling this rapid cavalcade of wonders, but somehow it stays fresh all the way to the end. Immortal line: “Fling him to the ape!”

Warning: this film has long been in the public domain, and there are a lot of crappy digital transfers out there. A lot of care went into restoring the Cohen Film version, and that’s the one I recommend.

See Part II of Silent Screen Swashbucklers here.