Cyrano de Bergerac (1950)

Cyrano de Bergerac

Rating: ***** (Essential)

Origin: USA, 1950

Director: Michael Gordon

Source: Alpha Video DVD

You’ve seen this, of course, probably more than once. If you haven’t smile, nod, and pretend you have, then tonight make the time to find it and watch it. It’s based on the 1897 play by French poet and playwright Edmond Rostand, who wrote the original entirely in verse, in rhymed couplets. It was a gigantic hit, ran for years and toured the world. In 1923 famous American stage actor Walter Hampden commissioned the New York poet and playwright Brian Hooker to create an English translation in blank verse, which became the standard English translation for the next half-century; Hampden, playing Cyrano, used it in touring productions throughout the 1920s and ‘30s. (Fun fact: as good as the Hooker version of Cyrano is—and it’s very, very good—there’s another fine English version that appeared in 1970 from none other than Anthony Burgess, the author of A Clockwork Orange.) The brilliant Puerto Rican actor José Ferrer revived the play on Broadway in 1946, winning a Tony award, reprised the rôle for a live TV production in 1949, and again for this movie version in 1950, for which he won the Oscar for Best Actor. The movie was an independent Stanley Kramer production, made on the cheap, and it’s been criticized for its low production values in an era of grand Hollywood epics, but really it looks fine and frankly it suits the material, opening out just enough from the staginess of the play to avoid theatrical claustrophobia.

By the time he made the movie, Ferrer had been playing the rôle of Cyrano for years, and really came to inhabit the part. He loves it, and his enthusiasm is infectious. The play was shortened somewhat to fit a feature’s run-time, with some new interstitial material written by Orson Welles (uncredited) to mask the transitions between acts; this included a brief scene between the Comte de Guiche (Ralph Clanton) and his uncle “The Cardinal,” who though unnamed is clearly intended to be Richelieu. Also added to the film were the swordfight with the “hundred” thugs and the fight with the Spanish at the Siege of Arras. For a low-budget production these were very well done, but this should come as no surprise considering the film’s fight director was the veteran sword-master Fred Cavens, who coached the fencing in just about every Hollywood swashbuckler from the silent era on. (Get this: Cavens coached Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., as Zorro in 1921, Tyrone Power as Zorro in 1940, and Guy Williams as Zorro in 1957!) Ferrer holds his own in these fights, and looks good doing it—and you can tell it’s him and not a double, because who else would have such a big nose?

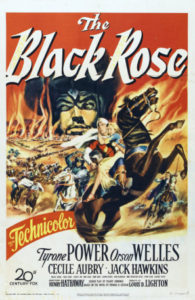

This movie works well as a spectacle depicting 13th-century England and parts of Mongolia and China. As an adventure or character-driven story, however, it’s not so good. This is one of those films in which the angry and stubborn protagonist is told at the beginning what he needs to do to find peace and purpose, spends the next two hours determinedly rejecting that advice, before finally embracing it in the last ten minutes of the picture. Lame! In this case, Walter of Gurnie (Tyrone Power), an illegitimate son of a Saxon lord, is the angry protagonist who’s suffered injustice at the hands of his Norman relatives. Edward II (Michael Rennie)—the King of England, no less—tells Walter he needs to put aside his hatred of the Normans for his own good and that of the realm and its people, but Walter angrily insists on leaving England to seek his fortune in distant lands—in far Cathay, if necessary, which he heard about from his Oxford mentor, Roger Bacon.

This movie works well as a spectacle depicting 13th-century England and parts of Mongolia and China. As an adventure or character-driven story, however, it’s not so good. This is one of those films in which the angry and stubborn protagonist is told at the beginning what he needs to do to find peace and purpose, spends the next two hours determinedly rejecting that advice, before finally embracing it in the last ten minutes of the picture. Lame! In this case, Walter of Gurnie (Tyrone Power), an illegitimate son of a Saxon lord, is the angry protagonist who’s suffered injustice at the hands of his Norman relatives. Edward II (Michael Rennie)—the King of England, no less—tells Walter he needs to put aside his hatred of the Normans for his own good and that of the realm and its people, but Walter angrily insists on leaving England to seek his fortune in distant lands—in far Cathay, if necessary, which he heard about from his Oxford mentor, Roger Bacon.