Thousand and One Nights

A Thousand and One Nights

Rating: ***

Origin: USA, 1945

Director: Alfred E. Green

Source: Amazon Streaming Video

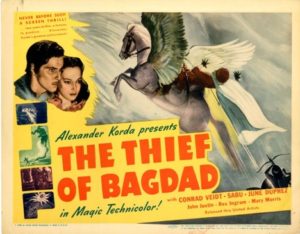

This is a tongue-in-cheek Arabian Nights fantasy that falls somewhere between send-up of and homage to The Thief of Bagdad, especially the 1940 version. Aladdin of Cathay (?), played by Cornel Wilde, is a vagabond street singer whom we first see crooning an ode to the desirability of a row of women for sale at a slave auction. This is tasteless by current standards, but it does serve to inform us that in this film, the rôle of women is strictly ornamental—with one exception which we’ll get to shortly. This singing Aladdin has a sidekick, a pickpocket named Abdullah played by Phil Silvers—yep, it’s Sgt. Bilko, black-framed glasses and all. Everyone calls him crazy because he says he was born 1200 years too soon, makes jokes about television and gin rummy, and tells the palace guards their turbans are “groovy.”

In a scene lifted right out of Thief of Bagdad, mounted guards clear everyone from the street at the approach of the princess’s elaborate sedan chair, because “No man may gaze upon her and live.” That, of course, makes Aladdin determined to see her—and one daring intrusion and two songs later, the vagabond and the princess (Adele Jergens, strictly ornamental) have fallen in love. He serenades her in a palace garden that, like many of the sets, is a virtual duplicate of the one for the equivalent scene in Thief of Bagdad. In fact, the whole look of the film, the architecture, the props, the bright costumes against the pastel backgrounds, is practically a love letter to William Cameron Menzies.

Soon enough the guards are shouting “Seize him!”, and Aladdin and Abdullah are on the run. In a mystic cave they meet a mystic mage with a mystic crystal, who sends them after a mystic treasure guarded by a mystic giant—Rex Ingram himself, fifty feet tall and looking exactly as he did playing the Djinni in Thief of Bagdad, chasing his puny prey and doing That Laugh. The treasure turns out to be a magic lamp (oh, right: Aladdin) that contains the best thing about this movie, a sassy red-headed genie played by Evelyn Keyes and named, er, “Babs.” Keyes, who is lively, clever, and ornamental into the bargain, effortlessly steals the rest of the picture, and no wicked vizier, sultan’s evil twin, or mystic mage can stand against her. Bonus: in the finale Cornel Wilde, who’d been an Olympic fencer in the 1930s, gets a chance to show us what he can do with a sword, and it’s quite impressive. Groovy, even.