Black Pirate

Black Pirate

Rating: *****

Origin: USA, 1926

Director: Albert Parker

Source: Kino Video DVD

The Black Pirate was a risky experiment with a new technology that went by the name of “Technicolor”—a risk that, in the main, paid off. It was also the first big-budget Caribbean pirate movie, and Douglas Fairbanks went all-in on an original story that drew heavily on Howard Pyle’s tales, drawings, and paintings, and on Stevenson’s Treasure Island—the best possible sources, really.

The film opens with a pirate crew plundering a captured merchantman, and immediately establishes that these sea rovers are bad, bad people, as atrocities are committed in the name of plunder and sheer bloody cruelty. The pillaged ship is sunk, its powder magazine exploded, after which Fairbanks, the sole survivor, makes it ashore to a desert island, where he vows to live for revenge.

This is the film that established the visual look of all Hollywood pirate films to follow—right up to the current day, really. Waistcoats and sashes, peglegs and parrots, eye-patches and cutlasses, tattoos, piercings, and questionable facial hair—it’s all here. And then there are the familiar tropes: treasure buried in hidden caves, dividing the spoils on the quarterdeck, drunken roistering, walking the plank—look no further for their cinematic origins.

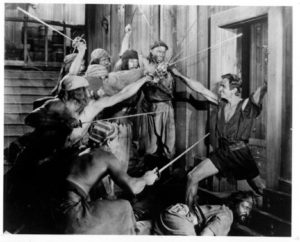

Posing as a cutthroat, Fairbanks boldly makes a bid to join the band of buccaneers, as they are conveniently burying their treasure on the island where he was marooned. He beats their best fighter in a fencing match—some nice sword-fighting, with some fine rapier-and-dagger work—and joins the crew. Challenged by a Basil Rathbone-cognate to show he understands that there’s more to piracy than swordplay, Fairbanks proves he has brains as well as brawn by taking a merchant ship by stratagem.

The stunts in this film are amazing, as Fairbanks swings through the rigging like Spider-Man. This is the movie where the riding-your-dagger-as-it-slices-its-way-down-the-sail gag was invented—it’s such a great stunt, he does it three times.

Clad all in black silks and leather, Fairbanks takes the name “the Black Pirate,” and sets out to become the pirates’ leader—and then immediately betray them. There’s a captive princess to rescue into the bargain, with whom he’s fallen in love at first sight. But his plans are foiled by a clever rival, and there follows a series of sudden reversals, clever ruses, daring escapes, and unexpected twists. Most unexpected of all, for Your Editor at least, is when Fairbanks, having escaped from the pirates, returns to rescue the princess in command of a long, slim galley rowed by three dozen body-builders clad mainly in shiny leather straps. And then, frankly, things just get weird. But the weird ending notwithstanding, this is a fabulous picture, grand and exciting, and not to be missed.