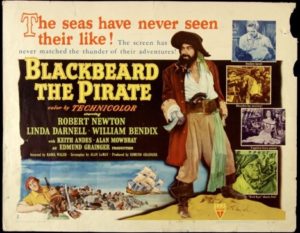

Blackbeard, the Pirate

Blackbeard, the Pirate

Rating: **

Origin: USA, 1952

Director: Raoul Walsh

Source: Amazon streaming video

On November 22, 1718, Edward Teach, the notorious pirate known as Blackbeard, was killed on his ship the Adventure during a fierce boarding action led by Royal Navy Lieutenant Robert Maynard. By the time he was brought down, Blackbeard had been shot five times and suffered twenty wounds from edged weapons. For the most famous image depicting this event, look no further than the painting by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris on the cover of your editor’s Big Book of Swashbuckling Adventure anthology.

Blackbeard’s career and death are also depicted in this film, in which Lt. Maynard, ordered to Port Royale in pursuit of Henry Morgan and the loot from the sack of Panama … wait, what? Whoa, this story is set in the 1670s, before Ned Teach and Rob Maynard were even born. In fact, this entire moving picture is nought but a tissue of lies! Avast! Bloody pirates—they’ll steal half a century right out from under you if you so much as look the wrong way.

History failure notwithstanding, this was one of the most popular pirate movies of the ‘50s, thanks mainly to Robert Newton’s unhinged and completely over-the-top performance as Blackbeard. Newton took all the mannerisms and speech patterns he’d developed for the rôle of Long John Silver in Treasure Island and cranked them up to eleven, frequently veering into farce and self-parody, but no less entertaining because of that. (So many “Arr”s!) Unfortunately, the rest of the film doesn’t hold up so well. The plot is sadly muddled, starting out with Maynard undercover chasing Morgan but captured by Blackbeard, along with Edwina, a pirate-captain’s daughter who’s secretly stolen Morgan’s treasure, all of them blundering about loudly at cross-purposes, and it never really gets sorted out. Characters’ motives change suddenly from scene to scene, people stranded on islands show up back in port without explanation, and even the big ship-to-ship showdown between Blackbeard and Morgan ends in an unsatisfying draw. It’s a mess.

One could overlook the ham-handed story if the performances supporting Newton were entertaining, but the rest of the cast is just bland and forgettable. Worst is Keith Andes, who plays Maynard, the English naval lieutenant and ostensible protagonist, exactly as if he were a tough-talking New York district attorney going up against the mob—imagine a slim Peter Graves but with no sense of humor. We’re supposed to root for this guy against Blackbeard and the other pirates, but it’s flat-out impossible. His intermittent romance with Edwina (Linda Darnell) is likewise arid and unconvincing, no matter how hard Darnell tries to look adoringly at him. Yeah, no.

At least there’s a lot of action, solidly directed by Raoul Walsh; the cutlass duels in particular are quite good. The shipboard scenes are also decent, with the quarters below decks properly close and cramped, including visits to the lazaret and the orlop (or, as Newton calls it, “the arr-lop”). And Blackbeard’s crew are as filthy and repulsive a set of brutes as you’re likely to see in the otherwise over-tidy 1950s, so bonus points for that. But you won’t be able to swallow the story unless you swallow a stiff rum or three first.

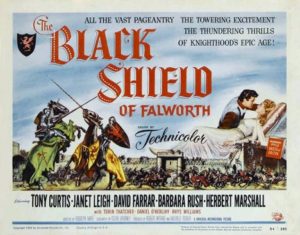

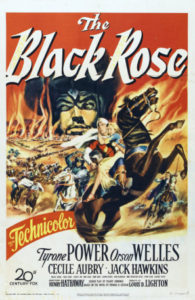

This movie works well as a spectacle depicting 13th-century England and parts of Mongolia and China. As an adventure or character-driven story, however, it’s not so good. This is one of those films in which the angry and stubborn protagonist is told at the beginning what he needs to do to find peace and purpose, spends the next two hours determinedly rejecting that advice, before finally embracing it in the last ten minutes of the picture. Lame! In this case, Walter of Gurnie (Tyrone Power), an illegitimate son of a Saxon lord, is the angry protagonist who’s suffered injustice at the hands of his Norman relatives. Edward II (Michael Rennie)—the King of England, no less—tells Walter he needs to put aside his hatred of the Normans for his own good and that of the realm and its people, but Walter angrily insists on leaving England to seek his fortune in distant lands—in far Cathay, if necessary, which he heard about from his Oxford mentor, Roger Bacon.

This movie works well as a spectacle depicting 13th-century England and parts of Mongolia and China. As an adventure or character-driven story, however, it’s not so good. This is one of those films in which the angry and stubborn protagonist is told at the beginning what he needs to do to find peace and purpose, spends the next two hours determinedly rejecting that advice, before finally embracing it in the last ten minutes of the picture. Lame! In this case, Walter of Gurnie (Tyrone Power), an illegitimate son of a Saxon lord, is the angry protagonist who’s suffered injustice at the hands of his Norman relatives. Edward II (Michael Rennie)—the King of England, no less—tells Walter he needs to put aside his hatred of the Normans for his own good and that of the realm and its people, but Walter angrily insists on leaving England to seek his fortune in distant lands—in far Cathay, if necessary, which he heard about from his Oxford mentor, Roger Bacon.