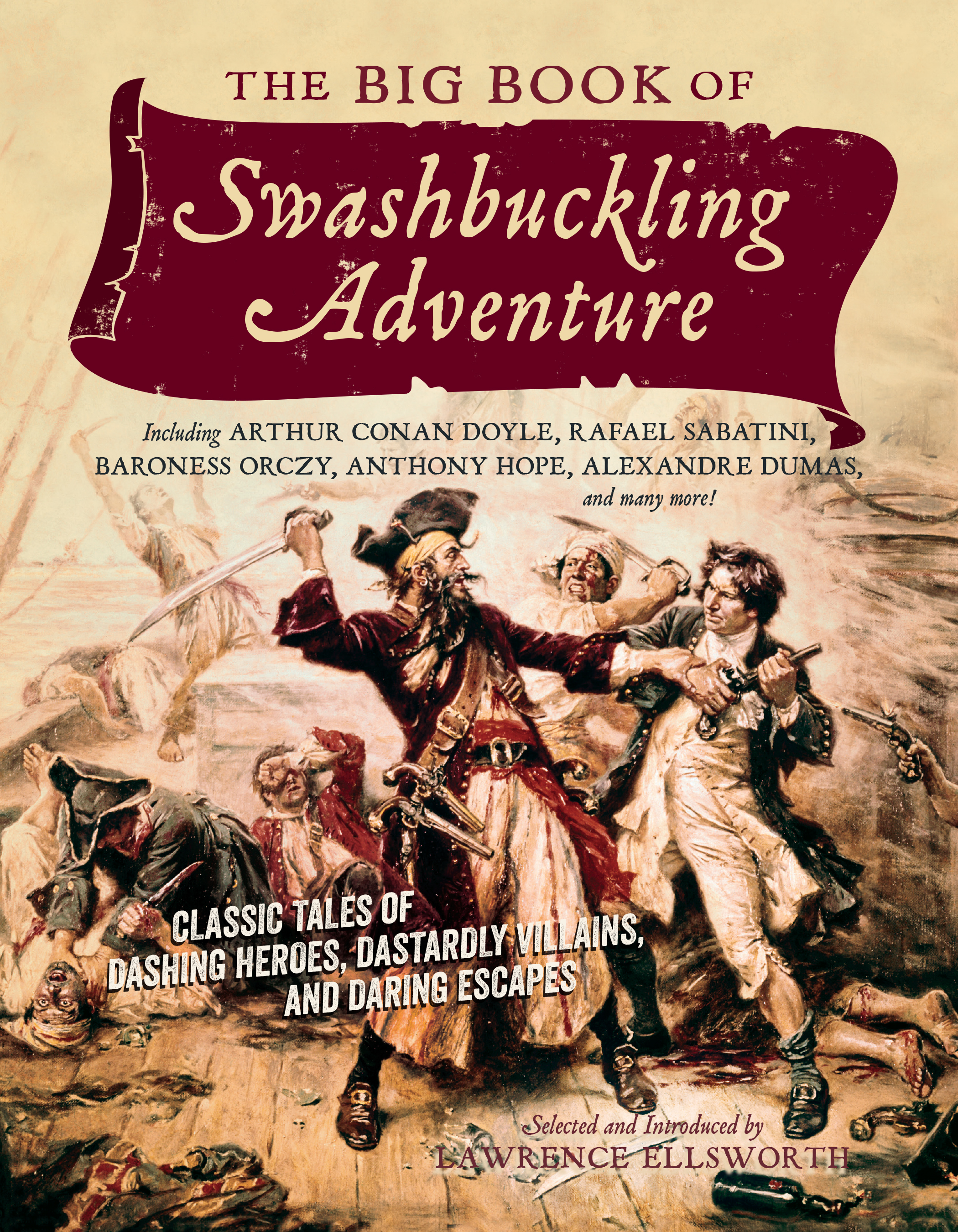

Compiling The Big Book of Swashbuckling Adventure

I’ve been reading and collecting swashbuckling adventure fiction for many years – my whole life, really. A couple years ago, while in the middle of a long (and still uncompleted) translation project, it occurred to me that I probably knew enough about the subject to be able to compile a pretty interesting anthology. The more I thought about the idea, the better I liked it, so I sat down and starting making notes.

I decided the anthology had to meet four criteria. First, it would need to catch the attention of contemporary readers, which meant including recognizable, marquee names, of both characters and authors. Second, it would have to be attractive to mainstream publishers, which meant inexpensive to produce (works in the public domain), and couched in a familiar, saleable format – in this case, a “Big Book,” a fat collection of at least 200,000 words. Third, for variety I wanted a good mix of pirates, cavaliers, and outlaws – and they all had to be cracking good stories that would hold the attention of modern readers. Fourth, not just any stories would do – I wanted carefully hand-picked works that weren’t overly familiar and would re-introduce some of my favorite forgotten authors to the 21st century.

To start with the marquee characters, I asked myself: when you say “swashbuckler,” what classic and instantly recognizable heroes spring to mind? Though there used to be more, nowadays it’s really only about half a dozen: Robin Hood, Zorro, the Scarlet Pimpernel, d’Artagnan, Captain Blood, and Cyrano de Bergerac (plus Long John Silver, but he’s really an anti-hero). Hey, I thought, I can do most of those!

Robin Hood: The Robin Hood tales commonly appear in the form of linked short stories, which was convenient for anthologizing, but the problem was there’s almost too much to choose from. Fortunately, once I looked into it the material winnowed out pretty quickly, as most of the retellings of the old ballads are either too juvenile, i.e., written for kids, or too familiar – for example, Howard Pyle’s versions, which have been continually available ever since their original publication in 1883. I thought I’d like to present the modern reader with a retelling from the beginning of the Romantic period, when interest in Robin Hood was revived by the British authors Sir Walter Scott and Pierce Egan the Younger. Scott’s popular take on Robin Hood appeared within a novel – Ivanhoe – and couldn’t be conveniently or coherently excerpted, so that narrowed it down to Egan. I selected his retelling of Robin’s encounter with Guy of Gisborne because it’s energetic and charmingly lurid, and most readers would recognize the name of the villain.

Zorro: The greatest 20th-century swashbuckler was created by the American pulp writer Johnston McCulley, a prolific author whose output included a number of Zorro novels and short stories. I like some of the short stories quite a bit, but most of them appeared in Argosy magazine in the 1930s, which put them out of the public domain. However, the first novel, The Curse of Capistrano, was available, and conveniently the beginning chapters could be excerpted into a nice, tidy introduction to the character. The Fox was captured!

The Scarlet Pimpernel: Like McCulley, Baroness Orczy wrote quite a few tales about her most famous hero, including a handful of short stories that were compiled into two collections that are rarely seen today. However, choosing one wasn’t so easy: the Baroness was also an accomplished author of Victorian mysteries, and most of her short stories about the Scarlet Pimpernel read more like whodunits than swashbucklers. After some tergiversation I finally settled on “The Cabaret de La Liberté,” as it builds up a significant head of suspense before its resolution.

D’Artagnan: I adore and revere Dumas’ stories of the Four Musketeers, and though he didn’t write any short stories about them, I could easily have excerpted a tale from the million words the master wrote in the novels between The Three Musketeers and The Man in the Iron Mask. However, I also wanted to include a bit of my own work in the anthology, and I had a way to do that, insofar as the longer project I mentioned above is a translation of Le Comte de Moret, a Dumas novel from late in his career that has no extant English version. The novel is, in its way, Dumas’ second sequel to The Three Musketeers, as it picks up right after the completion of that story, and though it doesn’t feature d’Artagnan and his three friends, it does continue the stories of Cardinal Richelieu, King Louis XIII, Queen Anne of Austria, and the intrigues of the royal court. And it introduces two new swashbuckling heroes in Dumas’ classic mode, the eponymous Comte de Moret and his right-hand rogue, Étienne Lathil. For the anthology I translated and excerpted the chapters that lead up to and conclude the novel’s climactic battle in the snowy Alps.

Captain Blood: Swashbuckler titan Rafael Sabatini’s two most famous characters are the scholarly pirate, Captain Blood, and the harlequin swordsman Scaramouche – but my collection needed more pirates in it, d’ye see, so I went for Captain Blood. Sabatini’s Captain Blood: His Odyssey first appeared in the United States as a series of stories in the peerless Adventure magazine, from which I selected the final one for inclusion in the anthology.

Cyrano de Bergerac: Here is where I struck out. Though we mainly know Cyrano today from the familiar Edmond Rostand play, he’s actually appeared in a number of other tales, but none of them are short stories, and I couldn’t find any novel excerpts that I thought were strong enough for inclusion. Well, not even Cyrano won every fight.

On to familiar or “marquee” authors. The swashbuckler ruled the bestseller list for a century from 1840 to 1940, but sadly not a lot of those authors’ names are recognizable today. Prospective readers of the Swashbuckling Adventure anthology would certainly know the name of Alexandre Dumas, and probably Rafael Sabatini and Baroness Orczy – all already covered above – but then where do you go? Fortunately, there are also some well-known authors who are remembered for other works but who also wrote swashbucklers, a list that includes the great Harold Lamb and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Doyle needs no introduction, but his greatest swashbuckler, Brigadier Gerard, is considerably less famous than the immortal Sherlock Holmes. But though Doyle earned his fame from his Holmes tales, he really wanted to do historical adventures, so after he killed off Holmes in “The Final Problem,” he turned to writing the Brigadier Gerard stories and historical novels like The White Company. Good news for us – and as a bonus, the Gerard stories are almost universally hilarious. “How the Brigadier Played for a Kingdom” added a welcome leavening of comedy to the anthology.

I’m not going to say much about Harold Lamb because our friend Howard Andrew Jones has already said it all, and better than I could. Suffice to say, if you haven’t read Howard’s compilations of Lamb’s historical adventure stories, you should do so instantly. As Howard himself pointed out to me, I could have picked a Lamb tale with more swashbuckling action than the story I selected, “The Bride of Jagannath,” but I like it because its dual-protagonist structure is different from most of the other tales in the anthology, and its setting, northern India, is a far cry from Europe or the Caribbean.

With the above stories selected the anthology was about half-full – or, given the amount of work remaining, half-empty. However, picking out the rest of the stories was actually my favorite part of the project, since that was where I got to introduce modern readers to the great but now-forgotten masters of the historical adventure story, many of whom were as just as good as the heavyweights mentioned above. These authors fell basically into two categories: those British writers whose popularity peaked around 1900, roughly between the reigns of Alexandre Dumas and Rafael Sabatini, and the American pulpsters who dominated the great Adventure and Argosy magazines during the teens and 1920s.

In the nineteenth century, after the runaway success of Walter Scott in Britain and James Fenimore Cooper in America, historical adventure wasn’t considered genre fiction: it was mainstream, part of the library of every upscale home. (This was why Doyle briefly gave up writing tawdry detective stories in favor of historicals – he wanted to do something respectable.) During the late 1800s there was a whole crowd of fine historical fiction authors in Britain working under the influence of Robert Louis Stevenson, who had taken the field by storm with Treasure Island and Kidnapped. His followers included excellent authors like Stanley J. Weyman, Anthony Hope, Sidney Levett-Yeats, and John Bloundelle-Burton, but while these gentlemen wrote plenty of novels, the problem for me was that they wrote precious few short stories. Stevenson was the exception: he wrote quite a bit in the short form, but none of it really qualified as material for this anthology. If I was going to adequately represent these authors, I was going to have to do some digging.

Stanley J. Weyman, arguably the best of this tight-knit club after RLS, wrote dozens of novels, but only two brief collections of historical short stories. From these I selected my favorite of his short works, “Crillon’s Stake,” which ably shows off his masterly grasp of character and setting – in this case, France in the late Renaissance. Also it’s a story about gambling, and no swashbuckling anthology should be without at least one of those!

Anthony Hope is best known today for his novel The Prisoner of Zenda and its even better sequel, Rupert of Hentzau. Hope was also mainly a novelist, but fortunately he wrote one little-known volume of short stories set in the same imaginary kingdom of Ruritania as the Zenda books. From that collection I drew the rollicking “The Sin of the Bishop of Modenstein,” which I confidently expect you’re going to love.

The Hyphen Boys, Levett-Yeats and Bloundelle-Burton, were less prolific than Weyman and Hope in the novels department, and wrote even fewer short stories, with no published collections. But eventually I found Levett-Yeats’ “The Queen’s Rose” in an 1899 issue of the British Cassell’s Magazine, and Bloundelle-Burton’s “The King of Spain’s Will” in the 1898 Longman’s Christmas Annual. Both are lost gems that I believe have never before been reprinted.

On to the American pulp writers – so inventive, so vigorous, and so delightfully lurid! We’d already included Harold Lamb and Zorro’s creator Johnston McCulley, but we could hardly compile an anthology of historical adventure stories without including at least one tale from “the King of the Pulps,” Henry Bedford-Jones. With H B-J there’s no shortage of stories to choose from – he wrote hundreds of them – but for balance I decided I needed one more tale of the age of piracy, so I selected his “Pirates’ Gold,” a 1922 novelette from that paragon of pulp magazines, Adventure.

Adventure was also the source for “The Black Death” by Marion Polk Angellotti, one of her series of about the English mercenary captain Sir John Hawkwood in Renaissance Italy. I particularly wanted to include one of her tales to show that, even a century ago, Baroness Orczy wasn’t the only female author who could rock a swashbuckler. Frankly, I think Angellotti was a better writer than Orczy, though she never created a character as indelible as the Scarlet Pimpernel.

With the American pulps properly represented, that brings us to my final author, the unclassifiable Jeffery Farnol, whose story is also the final selection in the anthology. Few contemporary readers have ever heard of Farnol, but I cherish his work. His writing was quirky – mannered, wry, and playful – and employed antiquated language and grammar in a fashion that most people either love or hate. His admirers included George MacDonald Fraser and Jack Vance, whose work I also love, so make of that what you will.

Anyway, though forgotten now, between 1907 and 1955 Farnol wrote almost fifty novels across an array of genres, including comedies of manners, historical mysteries (notably the fine Jasper Shrig series), historical romances (along with Georgette Heyer, he’s considered the inventor of the Regency romance genre), and a few wry, inventive, and wholly delightful swashbucklers. Farnol didn’t write many short stories, alas, and those he did aren’t right for this anthology, but I simply couldn’t leave him out, so I excerpted the climax of his brilliant pirate novel Black Bartlemy’s Treasure. I hope you’ll like it.

I could go on – the anthology will also be illustrated by fine, old engravings, and even includes a few poems – but I think I’ve presumed enough on your time for one article. The Big Book of Swashbuckling Adventure will be published in December, 2014, by Pegasus Books, in trade paperback and ebook formats. In the meantime I’ll continue to work on my translation of Le Comte de Moret, while gathering stories for a potential sequel anthology.

Half a King, by Joe Abercrombie. Del Rey, 2014; reviewed in the hardcover edition.

Half a King, by Joe Abercrombie. Del Rey, 2014; reviewed in the hardcover edition.