Adventures of Robin Hood: Season One

The Adventures of Robin Hood: Season One

Rating: ****

Origin: UK, 1955

Director: Ralph Smart, et al.

Source: Mill Creek DVD

This series, which premiered in 1955 in both the USA and UK, heralded a brief vogue for swashbuckling TV shows, most of them produced in Britain—but of them this is the only one that mattered, because it was smart and dependably entertaining, found a devoted audience, ran for four seasons in the fifties, and then for decades in syndication. (Its only significant rival was Disney’s Zorro.) Though shot in the UK with a British cast and crew, its producers were Americans whose politics leaned left, and most of its scripters were American screenwriters such as Howard Koch and Waldo Salt who’d been blacklisted in the U.S. They gave the stories an anti-authoritarian edge that accorded well with Robin Hood’s outlaw legend.

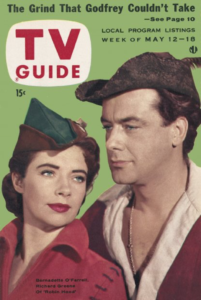

Much of the series’ success rested on the matinee-idol charisma of star Richard Greene, who invested the role of Robin with a charm and wry wit unmatched since Errol Flynn. With a foil in the equally charming Bernadette O’Farrell as Lady Marian Fitzwalter, and a determined and intelligent adversary in Alan Wheatley as the Sheriff of Nottingham, each episode’s brief (25 minute) morality play delivered solid entertainment week after week, for 143 episodes over the life of the series.

The first season (39 episodes) established the situation: Saxon noble Robin of Locksley, loyal to King Richard, returns to England during the corrupt reign of Prince John, and is outlawed. In resistance, Robin leads a band of Merrie Men from Sherwood Forest, fighting oppression with the aid of romantic interest Lady Marian and advisor Friar Tuck, both of whom are somewhat protected by their positions in society. This becomes the standard pop culture version of Robin Hood for a good twenty years, until the first of the revisionist Robin Hoods, Robin and Marian, in 1975.

The opening episodes that set the stage are among the best. In “The Coming of Robin Hood,” written by Ring Lardner, Jr., Locksley, “back from the Holy Wars,” finds that a Norman, Roger de Lille (a young Leo McKern) has usurped his domain; when Robin tries to reclaim them, an attempt to assassinate him kills de Lille instead, but Robin gets the blame and is outlawed. In “The Moneylender,” Robin joins a band of outlaws in Sherwood, converts them to robbing from the rich to give to the poor, and inherits their leadership when their chief, Will Scathlock, dies in an ambush that Robin had warned them was likely. “Dead or Alive” introduces Little John (Archie Duncan), with the traditional quarterstaff fight on the log bridge, while “Friar Tuck,” of course, brings that mettlesome priest (well played by Alexander Gauge) into the band—and thereafter the outlaws have two schemers in their number. Finally, episode five, “Maid Marian,” introduces Robin’s lady-love in her first full appearance, already adopting male guise and outshooting most of the outlaws.

Unlike most British shows of the period, Robin Hood wasn’t shot all on soundstages, with some exteriors set in the English greenwood in nearly every episode. The scripts are mostly sharp, with an edge lacking in most conformist 1950s teleplays, though most of the overtly comic episodes haven’t aged very well. The swordplay choreography is largely quite good, and archery is often central to the plot, which is gratifying—with the outlaws actually stopping to string their bows before going into action! And for a fifties TV show Lady Marian is quite assertive, capable with a bow, and shown to keep a French maître d’armes who trains her in handling a sword. Later episodes well worth your time include number 18, “The Jongleur;” 22, “The Sheriff’s Boots;” 36, “The Thorkil Ghost;” and what is essentially the season closer, episode 38, “Richard the Lion-Heart.” Note that DVD collections tend to jumble the episode order, which actually matters with this show, considering the way characters are introduced and developed; look online for a reference so you’re sure to watch them in proper succession