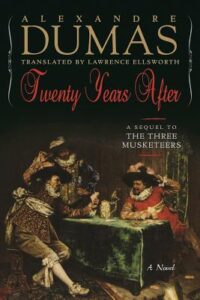

Book Three of the Musketeers Cycle

By Alexandre Dumas, Edited and Translated by Lawrence Ellsworth

Twenty Years After: Introduction

By Lawrence Ellsworth

In 1844 Alexandre Dumas, then age forty-one, had been a successful writer for almost a decade and a half, having made his mark first in the theater with sensational contemporary and historical melodramas. The rise of the feuilletons, French weekly newspapers that published episodic novels in serial form, gave him the opportunity to turn the lessons he’d learned crafting crowd-pleasing plays to popular prose. Dumas’s gifts were for engaging characters in plot-driven stories depicted with vivid scenes and crackling dialogue. More than that, he had a genuine feel for French history, and a knack for bringing it to life for his readers.

These virtues all came together in March 1844, when the first chapters of The Three Musketeers began appearing in the pages of Le Siècle, a Parisian weekly. The story was a runaway success, and the paper soon had to increase print runs to keep up with the demand. Once published in book form, The Three Musketeers was a global sensation, and Dumas was elevated from a mere successful writer to the ranks of history’s greatest storytellers.

At that time a great many serial novels were being published on both sides of the English Channel. What was it about Dumas’s novel that struck a chord with such a broad national, and then international audience? For one thing, its fast-paced and sweeping drama took maximum advantage of Dumas’s strengths as a writer, mentioned above. But beyond that, its quartet of quirky and charismatic heroes were immediately beloved by readers everywhere. Each musketeer expressed an aspect of Dumas’s own outsized personality, his boundless enthusiasm for life, romance, and adventure: the bold and clever d’Artagnan, noble Athos, jovial Porthos, and sly Aramis were vivid and engaging incarnations of archetypal adventure heroes, familiar yet uniquely and individually themselves.

And with these four characters, Dumas had created a tight-knit team of disparate personalities that was durable, flexible, and expansive enough to enable him to address, through their exploits, what he saw as life’s central challenge: how to find the courage to adhere to a personal code of honor despite the conflicting dictates of society and authority. How, in short, to do right.

The spectacular first Musketeers novel established Dumas’s core characters and their all-important interrelationship, that comradeship and commitment that made the Inseparables a byword for devoted loyalty. “All for one and one for all.” But the four musketeers were no Knights of the Round Table, no paragons of chivalry, they were recognizably real people with flaws as well as virtues, and when Dumas pitted them against the soldiers and assassins of repressive authority, the reader felt they were in genuine danger, at risk not just of failure, but of death. Against such enemies they had only their courage, their wits, and each other—and somehow, that had to be enough.

The serialization of The Three Musketeers concluded in July 1844 and was published in book form before the end of the year in both Brussels and Paris. By then readers and publishers were already clamoring for a sequel, and Dumas, after discussing it with his assistant Auguste Maquet, was ready to provide one. But when the first chapters of Twenty Years After began to appear in January 1845, it wasn’t quite what anyone had expected.

The Three Musketeers, in which the heroes are all between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five, is profoundly a novel of youth, its protagonists exuberant, passionate, and energetic, overcoming obstacles by sheer audacity. Dumas could have written a second book set right after the first, simply expanding upon the formula of youthful heroics, but the author, by then approaching his mid-forties, was more interested in how his most popular characters would face life’s complexities once they were past the simple moral clarity of youth. How would his heroes cope when confronted by the ambiguities and compromises of maturity? Excited by this idea, Dumas planned out what we would now call a character arc for each of his four archetypal heroes, a long saga set against the events of one of the most dramatic periods in French history, the rise of King Louis XIV. Twenty Years After was the first installment of this grand story, a tale that would run to over a million words, culminating at last in The Man in the Iron Mask. It was a bold and ambitious undertaking that took several years to complete, but pardieu! He pulled it off.

Back to the work at hand: at the end of The Three Musketeers, d’Artagnan has achieved his dream, an officer’s rank in the elite company of the King’s Musketeers—but he’s also suffered tragedy by his failure to protect the woman he loved, who was murdered by his enemies, and this shadows his achievement. When his comrades one by one leave the musketeers to go their separate ways, d’Artagnan falls into the immemorial routines of the career military officer, and the years pass by. Though he serves with bravery, even distinction, so long as Monsieur de Tréville is still Captain-Lieutenant of the King’s Musketeers, there’s no path for d’Artagnan to advance without leaving the company, which to him is unthinkable. So, he marks time for twenty years, a trusty weapon going to rust, until the events of Twenty Years After rouse him from his daze and propel him back into action.

What has changed? For one thing, old Tréville has finally retired, leaving a vacancy at the head of his company. For another, the stable regime established by Cardinal Richelieu and enforced by him on the fractious French has been steadily unraveling since his death, and the dire inequities and long-suppressed rivalries in the fraying social order have erupted into a seething low-grade civil war, the Fronde. D’Artagnan’s commonplace skills, those of a mid-level military officer, are little valued during ordinary times, but now opportunity knocks; it’s only in times of trouble, when extraordinary measures are called for, that d’Artagnan can find expression for his unique talent for bold and unorthodox stratagems.

So as the factions arm for battle, d’Artagnan once again has the opportunity to perform extraordinary services for the queen, for her son the young king—and, of course, for himself. But the resources of the orthodox military he’s served in for twenty years are of no use to him here, for he’s at his best acting outside of hierarchy and unrestrained by convention. D’Artagnan summons up his all old energy and audacity and hurls himself at the complex challenges of the new regime.

And … he fails. D’Artagnan fails, because times are not what they were, and the virtues of youth, no matter how skillfully deployed, are no longer enough to master the situation. Life has become complicated, and simple solutions cannot succeed.

However, d’Artagnan knows the solution, or at least part of it: to find his old comrades, the Inseparables, Athos, Porthos, and Aramis, and reforge the bonds of comradeship and loyalty they formed when they were all youths. But they have grown apart from each other with the passing years, even as each one has grown to be more indelibly himself in the process. And they are on different sides in the French civil war of the Fronde. Pride, ambition, and sheer time have opened gaps between the old musketeers, and d’Artagnan will find it no easy thing to bridge those gaps and draw them back together.

And even if he does—for how long?